update, 4.10.25:

Well, I think I’ve exhausted myself (and all 17,936 regular readers of this blog) on this one. I don’t expect to say more about BIP_RBA (“balls-in-play runs below average”) for a while (of course, expectations are fragile things. . . ).

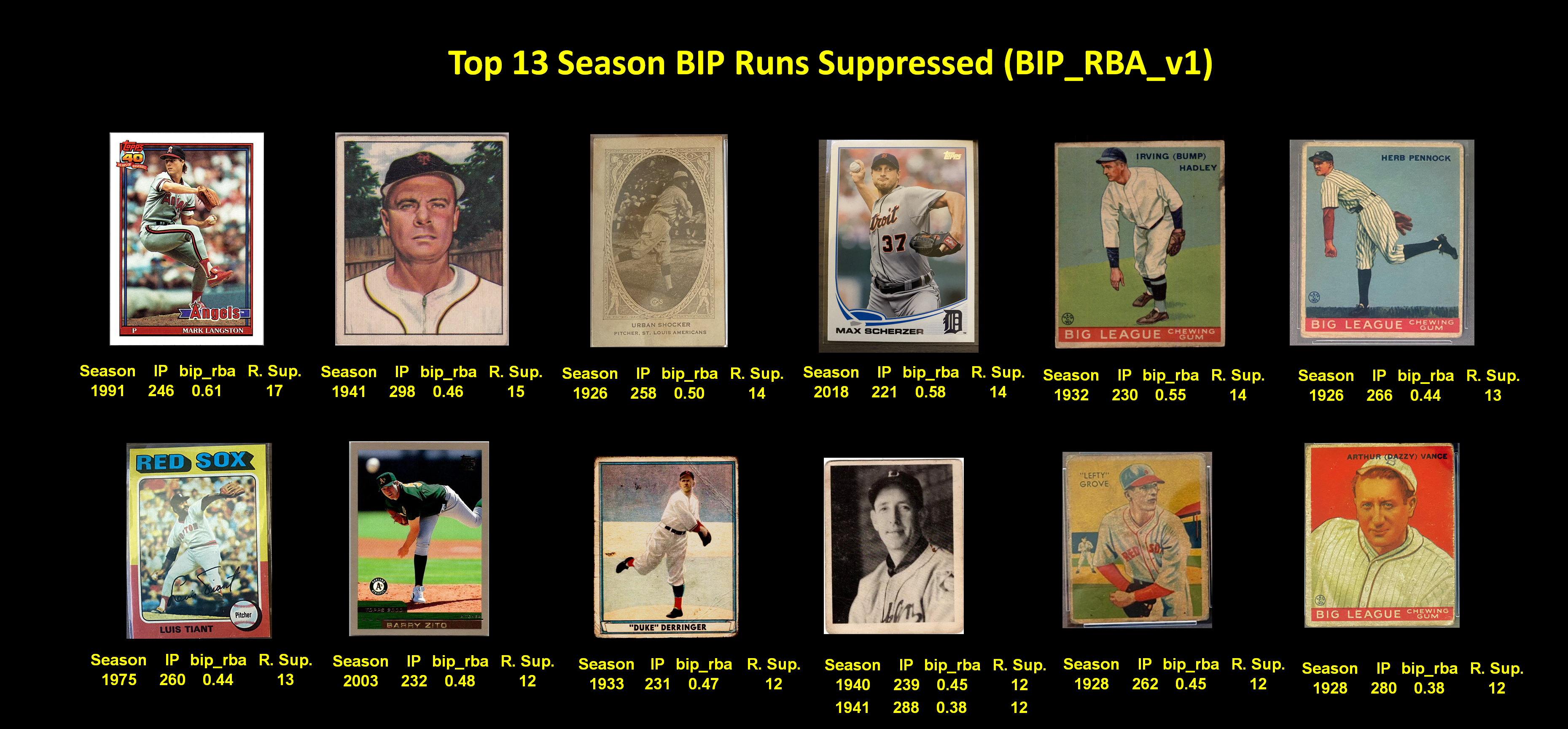

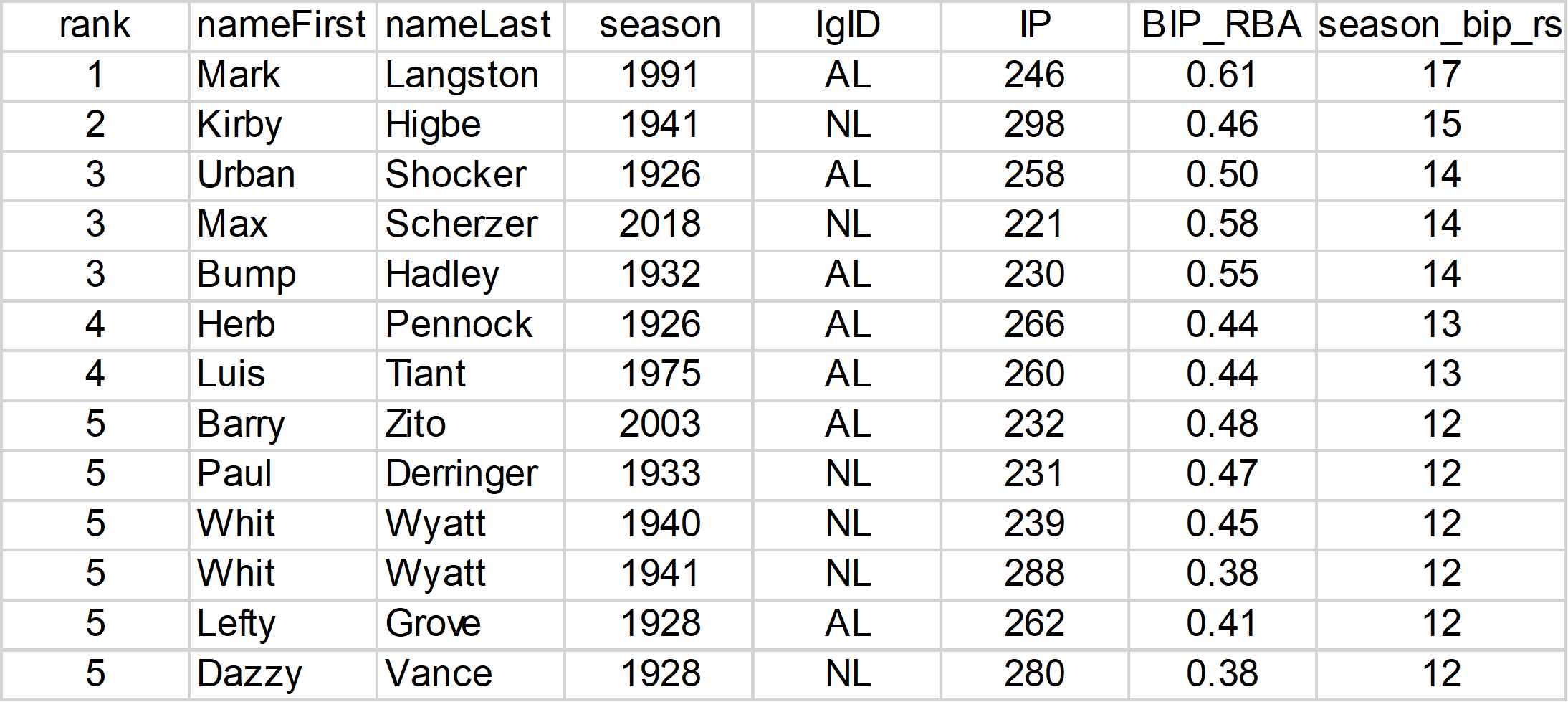

For fun, I’ve included the top 10—or really 13—single-season “BIP runs suppressed.” That’s the number of runs a pitcher avoided by virtue of his BIP propensities relative to a pitcher with average ones. The score is calculated by taking the pitcher’s BIP_RBA_v1, which reflects BIP runs below average per game, multiplying it by season innings pitched, and then dividing by 9.

But more importantly, here are some general reflections. I’ve divided them into two categories: (A) game-dynamic conclusions; (B) modeling conclusions.

A. Game Dynamics

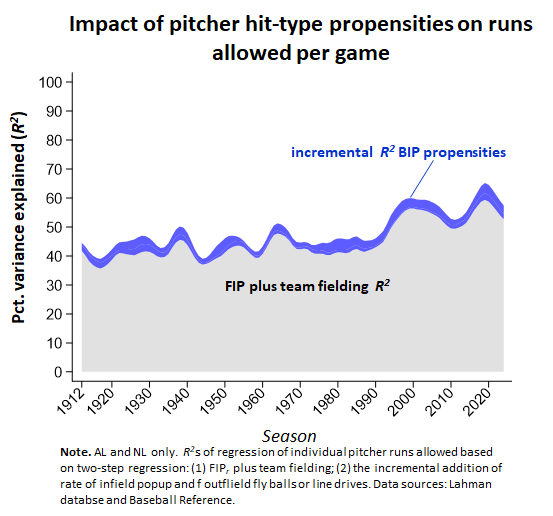

Whether a pitcher’s effectiveness depends on his tendency to induce more easily fielded hits has been a hotly debated topic for decades–ever since Voros McCracken formulated his famous conjecture that it doesn’t: what happens to a ball hit in play, he maintained, is entirely a matter of fielding proficiency and chance. Various commentators have challenged this thesis; indeed, I think most sabermetricians think the Voros claim has been effectively rebutted.

I don’t really think this is so, largely because, in all candor, the rebuttals have been very ad hoc and in some cases pretty attenuated. No one has tried, in particular, to statistically partial out the impact of team fielding before estimating BIP propensities or effects.

But like most, I have a hard time accepting McCracken’s thesis. That’s what motivated this project, which was designed to be more systematically empirical in engaging his position.

So here’s what I think:

1. Pitcher BIP-tendencies are real. The strongest version of McCracken’s claim—that pitchers exert no control over balls in play—is definitely false.

There is a high degree of reliability in how readily pitchers yield infield pop-ups (Cronbach’s α ≈ 0.80) and balls hit to the outfield (α ≈ 0.70) (and as a result ground balls to the infield, which is the residual category).

In addition, there is a lower but still practically meaningful regularity in the tendency of pitchers to limit the former and maximize the latter (α ≈ 0.60)—the combination that is necessary to suppress runs. The reliability of this tendency is lower because its components are in fact negatively correlated, meaning it’s not super frequent to find pitchers who consistently combine low outfield airball rates and high infield pop-up ones or vice versa.

We are talking about a relatively small slice of the regular pitcher population. But they do exist.

2. Pitcher BIP tendencies have a constrained and modest effect. The magic propensity to combine low rates of outfield balls in the air and high rates of infield pop-ups makes a modest contribution, not a huge one, to the success of the few pitchers who possess it. Actually, there are likely some middling-quality pitchers—like Al Leiter, Barry Zito and Ted Lilly—who owe their careers to this ability. But no one can really be seen as dominant as a consequence of it.

The reason I say this is that the run-suppression totals are just too small. The best pitchers probably saved no more than 70 runs over the course of their careers by virtue of this skill. That’s 7 total wins for their team. It might actually add up to a WAR of +10 or so (because WAR is calculated by reference to “replacement” players and not “average” ones). But Clayton Kershaws, Randy Johnsons, and even Louis Tiants and Catfish Hunters have to be doing more than inducing “weak contact” to put together highly successful careers. (I suppose it is possible that measurement error is attenuating the BIP_RBA effect size; but my initial foray into team-level effects, which are less noisy, makes me skeptical of that.)

Put these two points together, and I guess I’d credit McCracken with the better position in the big argument over his work. Empirically speaking, by far–and I mean really really far–the most important factor in a pitcher’s ability to suppress runs is his ability to keep balls out of play, as measured by fielding-independent pitching metrics like FIP.

3. The “big mystery” persists. That conclusion means, too, that what I regard as the biggest mystery of pitching success over the course of modern AL/NL history remains: what exactly made elite pitchers consistently successful before the advent of today’s style of punch-out pitching? For decades, the best pitchers didn’t amass huge strikeout rates yet managed to demonstrate their superior talent consistently for season after season.

Actually, BIP_RBA suggests that some 1930s pitchers might have been doing it to some extent on the basis of “soft contact.” Red Ruffing, Carl Hubbell, and Lefty Gomez, in particular, demonstrated a consistent—but still, in my view, relatively modest—ability to suppress runs by inducing easily fielded ground balls.

But the 1950s are a complete and utter mystery. That was a period in which BIP_RBAs were uniformly low. So inducing easily fielded batted balls isn’t the answer to how Warren Spahn, Robin Roberts, and Whitey Ford succeeded.

Yet FIP doesn’t really seem to be either. Spahn was actually second in 1950s FIP—but occupied the top tier with a variety of pitchers of much less accomplishment. Roberts and Ford were further down the list, behind numerous pitchers of decidedly less ability.

Yet none of them ever really excelled in BIP_RBA, either.

What’s more, contemporary era—post 2000 pitchers—are BIP_RBA monsters! For them, FIP really does furnish a compelling index of achievement. Yet many of the ones with the highest BIP_RBAs also had great FIPs. So it doesn’t seem—consistent, again with McCracken’s thesis—that the power to induce “weak contact” has ever really matched up with fielding-independent pitching as a determinant of success.

Argh! This mystery will never be solved! (I don’t really believe that.)

B. BIP_RBA model performance

1. Period sensitivity. Again, the late-1920s through 1930s seasons along with the post-2000s ones feature the most potent BIP-propensity effects, likely because those are periods of high run scoring. But how players rank and exactly how many runs they were suppressing, especially for the periods in between, turn a lot on how seasons are binned. Binning is necessary to determine stable model parameters; there is too much volatility season-over-season to make the calculations on a yearly basis.

I have settled on a specification of “BIP eras” that correspond pretty closely to points between which the overall contribution of BIP propensities to runs per game remained relatively consistent. But because there are lots of jumps, that resulted in 14 distinct periods, 14 distinct sets of parameters. Small adjustments of the starting and ending points for those periods can make a noticeable difference, particularly, again, for pitchers in the 1940s-1990s.

Indeed, I plan to keep trying to identify the “best” theoretical and statistically stable set of BIP eras. When I do, expect the rankings I’ve already generated for “top 10 career” and “season” BIP run-suppression to shift (although for sure you’ll see Kershaw, R. Johnson, Ruffing, Gomez, and Hubbell among the leaders; that’s a super robust result).

But the bottom line is that, for now, I have more confidence in BIP_RBA_v1 as a metric for empirically confirming that BIP tendencies matter (modestly) than I do in it for measuring with precision exactly what those tendencies contributed to runs suppressed in individual cases. So the latter project remains.

2. League differences don’t seem to matter. This surprised me. I would have thought that AL and NL parameters would vary considerably over the five-decade span in which the AL alone had the DH. But the addition of league-specific interaction terms to the relevant model parameters didn’t seem to improve model fit. Maybe more tinkering will reveal that league effects matter after all. But for now, it seems to me that the propensity to induce more infield-pop ups and avoid outfield air-balls had roughly equivalent impacts across both leagues at all points, which is different from what I anticipated but not really shocking.

* * *

Well, that’s it for now. Likely I’ll continue to refine and eventually draft a paper (just as I did on the phenomenon of “fielding shrinkage” in the period after baseball’s “Great Transformation”). I’ll let you know if something really noteworthy happens, but for now I will seek to enlarge my knowledge by examining other topics.

Nevertheless, if you see something noteworthy in this area, definitely let me know. If you want to look for something, you know where the data are!

BTW, I’ll soon add my Retrosheet “ball in play” decoder so that others don’t have to go through the headache that I did of constructing a coding system from scratch. I believe strongly that the elements of knowledge generation should be shared freely by curious and reflective people; holding such matters close not only constrains advancement of collective understanding but conceals from correction one’s inevitable missteps, a prospect that ought to really bother anyone whose goal is to learn.