So this is definitely the place to start. With these two enchanting cards.

They supply everything that this endeavor—a tiny little site; a wholly personal tribute to baseball, but glad you are here—is about.

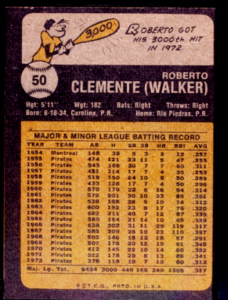

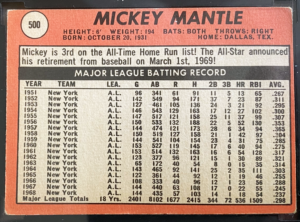

Start with what could seem like the most prosaic element of these cards’ appeal: when turned over, they report the entire careers of these two baseball giants. Every season is there. All the times Clemente topped the .300 threshold. All the times Mickey belted, 30-, 40-, and 50-plus home runs.

Plus the totals. Five hundred and thirty-six home runs. Three thousand hits; 3,000 exactly. . . .

Having it all there really does make them special. That’s because baseball, more than any other team sport conveys the magnitude of its stars’ accomplishment with literal representations of magnitudes. Over the game’s history, these numbers—especially key benchmarks: 200 hits; .300; 100 RBI; 40 home runs; 20 wins; 2.xx ERA etc.—have become potent tokens of player accomplishments.

Historically, the almost mystical communicative power of these digits is what has made baseball so compelling to many fans. Countless American schoolchildren (I certainly was one) learned to do complicated feats of division—and to love, not loathe, decimals—from computing baseball statistics. Baseball cards were the primary carriers of those mesmerizing numbers.

In addition, having access to a whole career’s worth of those numbers on a card was really rare. Unheard of, in fact. Now career-retrospective cards get produced, I guess. But they didn’t then.

Cards were made for active players. They reported the featured performer’s stats for last season and (by the mid-1960s) all his earlier ones.

But if one wanted to ponder the entirety of a past player’s career as communicated by 20-odd rows of numbers, one had to track down the Baseball Encyclopedia. Even if one were lucky enough to own this majestic tomb, it was destined to soon become woefully out of date, if it wasn’t already at the time one acquired it at a used bookstore. Getting access to those special numbers, then, was a lot harder than simply Googling a player online.

Here’s another thing that makes these cards the place to start: they are beautiful.

I don’t mean aesthetically, necessarily. They are very attractive (I think) but there are scores of other cards (parts of sets produced in the 1930s and 1950s) that come closer to being genuine artistic works.

These ones are beautiful because of their cultural meaning.

You feel all of what Mantle and Clemente contributed to the shared experience of Americans—of all sorts of backgrounds—when you simply hold them. And you feel that in part because you are conscious that others feel that too when they contemplate these simple pieces of cardboard. . . .

Lastly, and relatedly, we start here because the cards are linked to stories.

Lastly, and relatedly, we start here because the cards are linked to stories.

Clemente’s is the most familiar. How he died on New Years’ eve of 1972, when the plane he had chartered to personally deliver emergency aid to earthquake-ravaged Nicaragua crashed at sea amidst a furious storm.

Clemente was issued a card—a normal one—for 1973, a season he would never play. And if you turned it over, you saw that he had ended the 1972 season with exactly 3,000 hits—one of the numbers that certify a hitter as one greatest who ever played the game.

Mantle’s card has a story, too, one fewer people know. It was produced by Topps (by then the Microsoft, or better the AT&T, of baseball-card manufacturing) in anticipation that he’d play in 1969. His retirement—while not premature; everyone knew he was a spent force seasons earlier—came as a surprise at the start of spring training that year.

Actually, though, it was part of a conspiracy! Between Mantle and the Major League Baseball Players Association. Mickey had resolved to retire months earlier. But at the behest of the players union, he had held off on announcing it so that he could lend his immense status to a contract-signing boycott in response to the owner’s refusal to sustain their (already modest) level of contributions to the players’ pension fund.

The pension was meagre, but it meant a lot to the vast run of players, most of whom had careers much shorter than Mantle’s and who earned salaries that were literally an order of magnitude smaller than his. And because it meant that much to them, Mickey flexed his superstar muscle one last time, on their behalf.

The owners, worried about loss of television revenue if the season had to be postponed, relented. Then Mickey told everyone the news: he was done.

And that’s how a card that captured Mantle’s whole career came to be.

Maybe you didn’t know this story?

Telling it and others, with cards that are rich in cultural meaning, which they convey through compact little rows of numbers, is what this site is about.