1. The bottom-line of this post is simple and stark: the impact of differences in the quality of major league fielders has been precipitously falling for decades and is at this point of negligible consequence for how teams fare over the course of a season.

It’ll take some space to lay out the empirical evidence, and I’ll try to confine myself here to the essentials. I have uploaded the data and analysis script relied on so others can assess the soundness of my conclusion and investigate alternative theories.

2. Before I start, though, I feel impelled to acknowledge the modest role I played in prying this inference loose from my own data.

I initially intended only to compare the relative predictive power of Baseball Reference’s pre- and post-2003 measures of defense proficiency.

For seasons before 2003, BBR uses “Total Zone Runs” (TZR), which is based on sabermetrician Sean Smith’s heroic hand-coding and analysis of the game-play descriptions publicly available on Retrosheet.org.

The fielding metric used by BBR after 2003 relies on “Defensive Runs Saved” (DRS), which is derived from a proprietary model that the company Baseball Info Solutions uses to analyze its private stock of digital evidence on the probability that batted balls will be turned into outs.

I discovered and was prepared to report that TZR explains a substantially larger proportion of the variance in runs allowed than does DRS. But when I previewed a small portion of my findings for Smith, he was gracious enough not only to respond but to propose an explanation quite different from the one I was suggesting: this disparity in explanatory power, he surmised, might be attributable not to differences in the quality of the two measures (my thought) but instead to the diminishing role that fielding plays in averting runs as pitcher strikeout rates have increased.

This post is a summary of the data analyses I performed that convince me that Smith’s conjecture is correct (although of course he bears no responsibility for any missteps in my analysis or reasoning).

This post is a summary of the data analyses I performed that convince me that Smith’s conjecture is correct (although of course he bears no responsibility for any missteps in my analysis or reasoning).

3. The core defensive component of BBR’s calculation of player WAR is “rfield.” The measure represents the number of runs a player’s fielding saved his team.

I measured the contribution rfield made to variance in runs allowed at the team level for every AL/NL season since 1900. My principal motivation was to investigate the oft-stated (but never seemingly tested) skepticism about defensive WAR metrics for seasons prior to the advent of digitally informed analyses of fielding proficiency.

The data did not bear out such skepticism. Controlling for “field-independent pitching” (FIP), the pre-2003 TZR version of rfield explained upwards of 30%, and for some periods even 40%, of the variance in teams’ runs allowed. Over the course of its use, in contrast, the DRS version explains only 10% of that variance, and in recent years even less.

But as Smith hypothesized, that doesn’t show TZR is superior to DRS. The reason is that the difference in variance explained is attributable to the growing contribution of FIP (which, as anyone reading this likely knows, rates pitching proficiency as a function of strikeouts, walks, hit batters, and home runs allowed).

Added together, FIP and rfield explain between 80% and 90% of the variance in runs allowed across the vast majority of seasons both before and after 2003. That’s a remarkable thing in itself! But the point that bears notice here is the relative proportions of that variance explained by each. As can be seen in Figure 1, the share attributable to rfield (the region above the dashed line) shrinks dramatically while that attributable to FIP (the region below) expands to make up the difference.

It’s difficult to say exactly when this shift started and how quickly it progressed because the explanatory power of rfield suddenly drops to a negligible amount for a good portion of the 1990s. It was around then that Smith substituted for his own coding system a new feature of Retrosheets that purported to identify the fielding “zone” of balls in play. As Smith recounts in his recent book WAR in Pieces, he himself subsequently became convinced that those data were not reliable and stopped using them.

By 2000, the rfield dark ages had passed and the TZR measure rebounded. Although rfield still explains over 20% of the variance in runs allowed for the entire period from 1900 to 2002, it is probably a good idea not to rely on it for the decade of the 1990s. By the same token, if one’s goal is to assess the true power of rfield as an instrument for measuring the impact of fielding proficiency before the advent of digitally based metrics, it is important to recognize how dramatically including the ’90s will bias downward any assessment of TZR’s strength.

It’s probably safe to assume that rfield declined in influence relative to FIP in essentially a linear fashion over the course of the 1990s. The impact of FIP remains observable throughout and traces a linear path that had in fact already started by the 1980s.

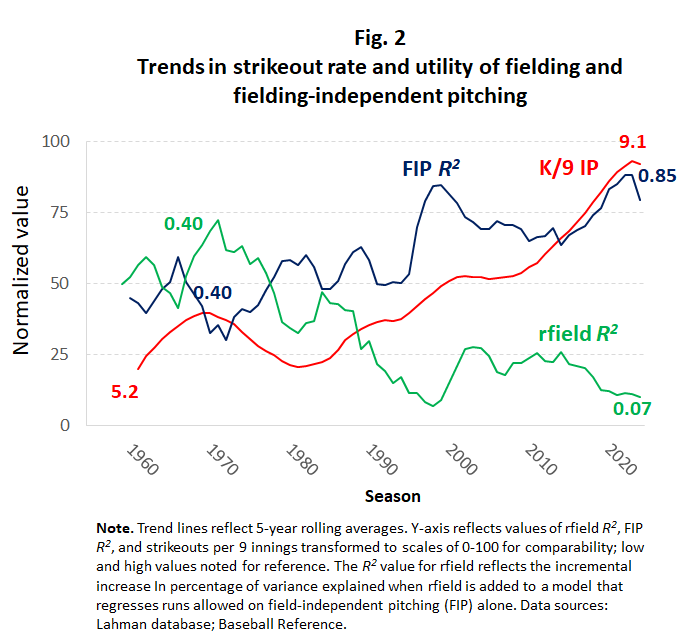

This was the same period when the rate of strikeouts began to rise appreciably. That makes perfect sense, of course, since strikeouts is one of the principal elements of FIP. Another visualization—one that juxtaposes changes in the explanatory power of rfield and FIP along with changes in the rates of strikeouts—confirms the rapidly evolving nature of run prevention in major league baseball: from near parity between fielding and pitching at mid-century to the decided domination of the latter over the former (Figure 2).

So how much has fielding’s contribution withered as a result of the onslaught of strikeouts in major league baseball? Seventy-five percent seems like a conservative estimate: between 1955 and 1980, 30% of teams’ runs allowed was attributable to the skill of their fielders; but by the decade that ended in 2024, fielding proficiency accounted for less than 7% of that variance.

That doesn’t mean, of course, that fielding competence is now irrelevant. Obviously, if a team assigned its fielding to a group of fans randomly selected from the bleachers, it would get demolished.

But what the shrinking contribution of fielding to avoiding runs does mean is that the difference in skill between the masterful glove men of, say, the Orioles of the late 1960s and early 1970s and that of a team of below average rivals would today make surprisingly little difference in how the two teams end up at the end of a 162-game season.

4. Indeed, it’s possible to quantify how much the impact of outstanding as opposed to mediocre fielding makes to a team’s success. But because I’ve already gone on too long, I will leave that for another post. In it, I will also discuss the related topic of rfield inflation, which refers to the overstated impact that rfield scores attribute to individual players’ fielding in recent decades.

But before I stop, I again want to acknowledge my gratitude to Sean Smith. Not only for his kind and very enlightening advice about what to look for in these data, but also for filling the world with valuable information about the measurement of baseball performance and for personally modeling how one should go about producing it.