Okay, I promised to say something about Balls-in-Play Runs Below Average (BIP_RBA) and opponant Batting Average for Balls in Play (oBABIP). But I don’t plan to say a lot.

First, BABIP is an annoyingly uninformative measure. Like ERA, oBABIP merges the combined efforts of a pitcher and his fielders.

Voros McKraken famously posited that the pitcher should in fact get no credit for a low oBABIP (or high one): what happens to a ball after a batter connects with it is entirely a product of fielding proficiency and chance, he argued (for a while anyway). Opponent BABIP is one of the fronts on which the battle over his thesis has been waged.

Indeed, I was motivated to develop BIP_RBA to try to assess the extent to which a pitcher should be credited for the effect of batted balls independent of the fielders who back him up. But because oBABIP needs the help of a valid BIP_RBA before we can settle the dispute over its relationship to pitcher effectiveness, pitchers’ oBABIPs can’t help us to validate any candidate BIP_RBA.

Second, oBABIP is not an intrinsically important measure—at least not if one has a BIP_RBA. It is of interest only as a proxy (a very imperfect one) for how the type of contact a pitcher allows affects runs allowed. BIP_RBA seeks to estimate that relationship directly. If we can be confident in that metric, then it won’t be necessary to rely on oBABIP for a guesstimate.

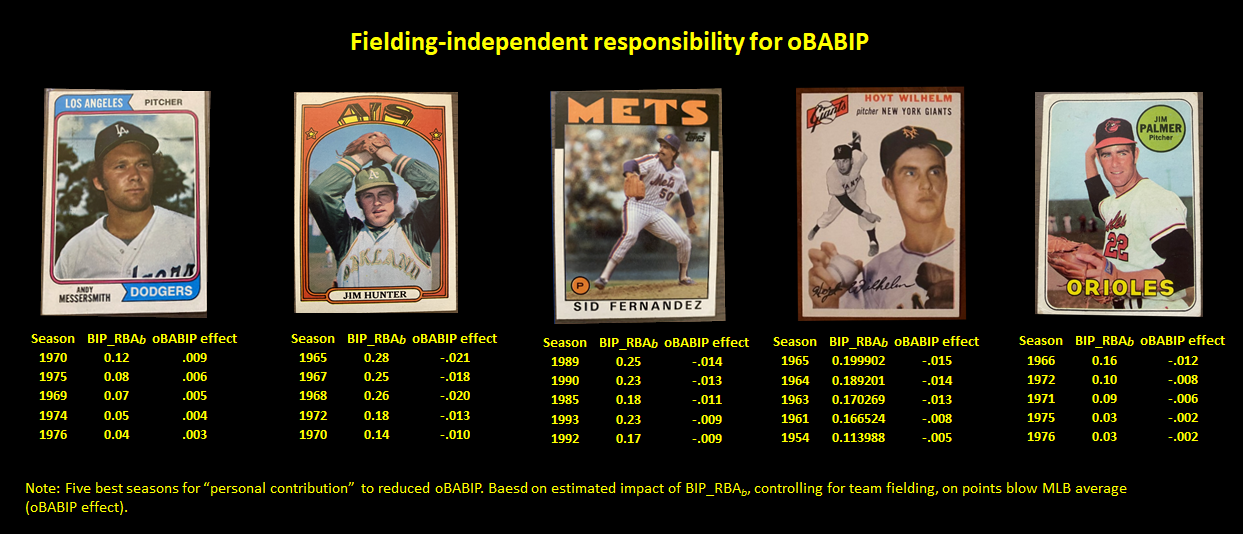

Third, even assuming oBABIP does tell us something about pitcher proficiency, the evaluation of raw oBABIPs won’t disclose the relative proficiency of different pitchers across time. This is due to the familiar problem of skill-unrelated variability in performance metrics based on changing game dynamics and conditions.

The most direct way to solve this problem is by standardizing those metrics. Standardization puts performances from periods characterized by skill-unrelated variance on a common scale. I’ve done that with batting average, OPS, fielding-independent pitching, and even strikeouts per 9 IPs.

I could do it with oBABIP, too, obviously. But because oBABIP is annoyingly uninformative and a needlessly indirect measure of pitcher quality on runs allowed, what would be the point of doing that?

But of course it is still fun to look at how raw oBABIPs relates to BIP_RBAb! So I have.

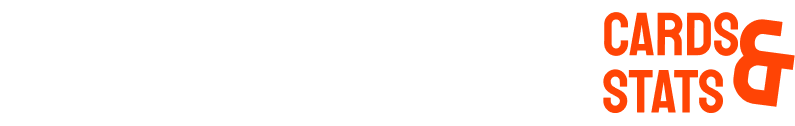

For this purpose, I simply regressed the single-season oBABIP of every AL and NL pitcher who threw 100 innings or more on (1) the best available metric of his team’s fielding prophecy (we should call that something; how about BAM_TF?) and (2) his BIP_RBAb. (Unsurprisingly, because BIP_RBAb already takes BAM_TF into account, these two predictor variables were uncorrelated with one another.) The BIP_RBAb coefficient in the regression can thus be used in a straightforward manner to estimate a pitcher’s personal contribution, independent of his supporting fielders, on his oBABIP relative to the MLB average for a particular season. (If I really cared only about oBABIP, though, I think it would make more sense to regress it on individual pitcher ball-in-play types team plus team fielding; but I wanted to see how BIP_RBAb performed in this task. If you want to do it, go ahead!)

What can we say based on this analysis?

Well, one pitcher’s who likely deserves a lot of credit for his career low oBABIP is Catfish Hunter. Hardly a punch-out sort of hurler, Hunter managed to induce lots of soft contact—four seasons above the 90th percentile in BBIP_RBAb and three others above the 80th. These marks—good for as much as a quarter of a run per game below average—typically translated to 10 to 20 points of suppressed oBABIP. That’s likely a good chunk of the reason Hunter’s career oBABIP (.246) ranks second for pitchers with 1,000+ IPs.

Sid Fernandez’s (.250) ranks 3rd. He also earned that mark. His multiple seasons above the 90th percentile in BIP_RBA (also good for about 0.25 runs below average) shaved 10 or more points off the BABIPs of opposing hitters in individual seasons.

Jim Palmer, on the other hand, didn’t do much to early is place as number 5 on the all-time oBABIP list (.251). He didn’t even compile one season at or above the 80th percentile in BIP_RBA. Maybe Brooks Robinson’s name should be inscribed over his on the all-time oBABIP list.

Hoyt Wilhelm, number 4 on the list (.250), was a batted-ball tamer of the first order. I noted that in the last post, on knuckleballer’s BIP tendencies.

Andy Messersmith is number 1 on the oBABIP list (.243). How’d he do it? That’s a mystery BIP_RBAb won’t solve, I’m afraid. The metric furnishes no evidence that the balls he launched toward batters were more likely to end up in a fielder’s glove than were anyone else’s. Maybe he was lucky enough to be backed up by superb fieldes his whole 12-season career across four franchises but that seems awfully unlikely.

Aw, that’s enough.

If you want to learn even more, though, feel free to check out the BIP_RBA/oBABIP connection for yourself—I’ve updated the BIP_RBA data page for your enjoyment. Tell me if you find something you consider interesting!