I’ve been sucked into the BABIP—batting average for balls in play—rabbit hole.

At any period in big league history, variation in BABIP and oBABIP (opponent batting average for balls hit in play)—contribute a substantial amount to runs and runs allowed. So naturally, one wants to try to explain them.

Voros McCracken is famous for the thesis that pitchers have no impact on BABIP. If a hitter makes contact with the ball, nothing a pitcher has done is going to affect it, making outcomes a mix of chance and fielding quality.

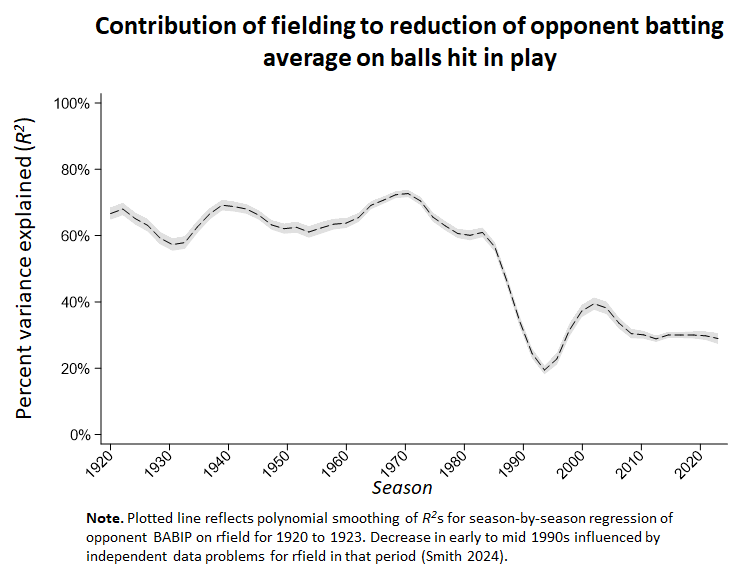

Well, for sure, variance in BABIP has historically been substantially influenced by fielding proficiency, as measured by rfield (runs saved by fielding).

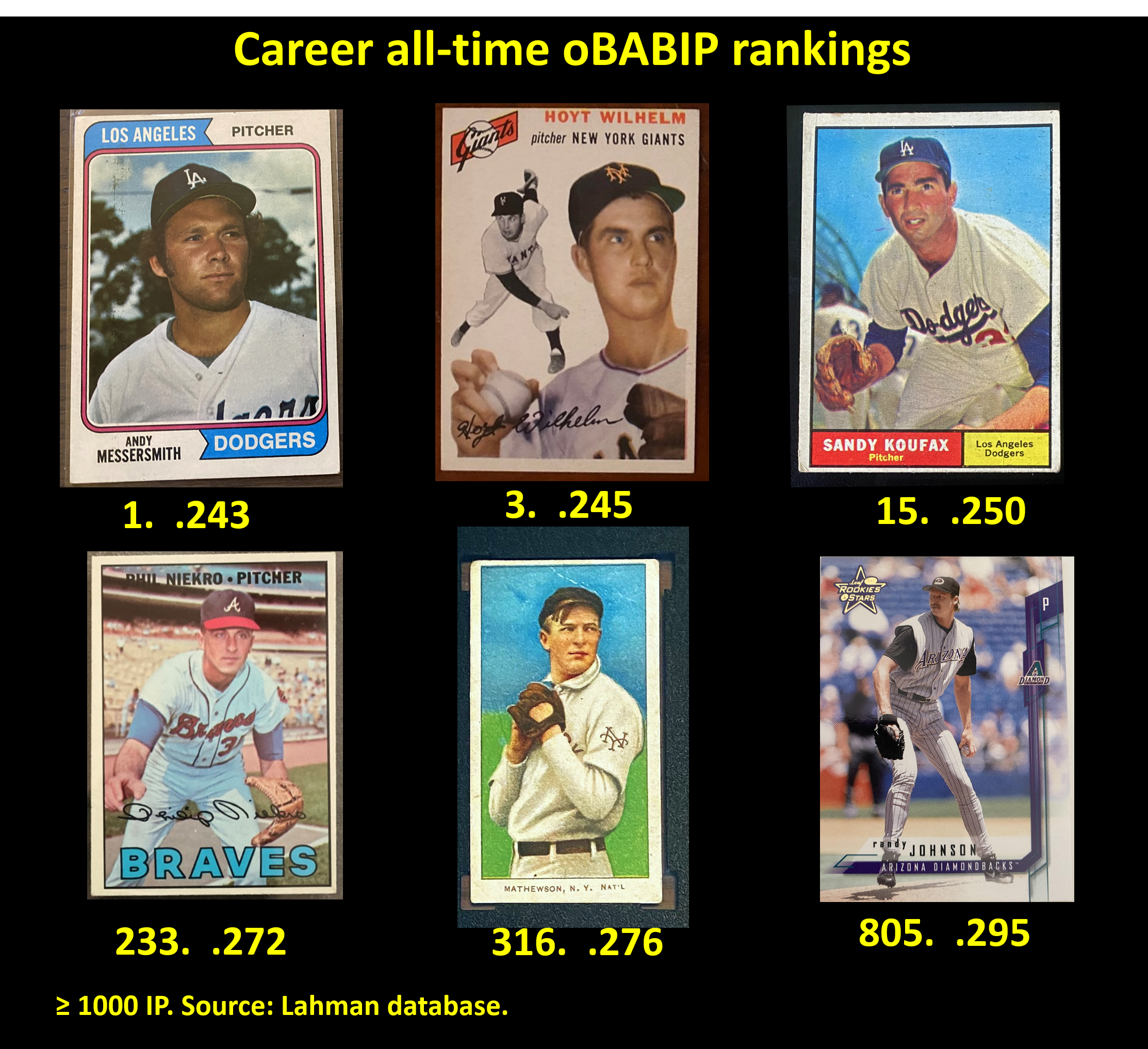

And I think most would accept now that either pitching proficiency contributes a small bit to oBABIP or that some small fraction of pitchers have a moderate impact on it even if most (even most very good ones) have none.

But what I want to understand is this:

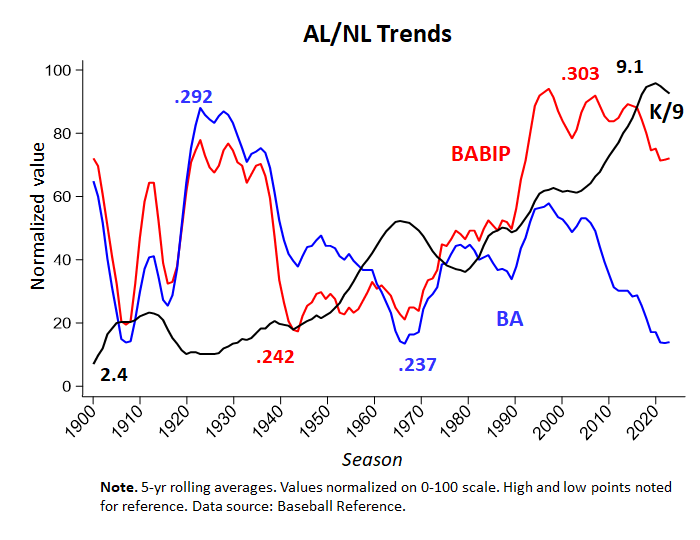

For most of baseball history, BABIP and batting averages were tightly yoked. That seems pretty logical: if a player has a high batting average, then he probably has a high BABIP, particularly since home run hitting alone (home runs being excluded from BABIP) can’t by itself contribute that much to a high BA.

For most of baseball history, BABIP and batting averages were tightly yoked. That seems pretty logical: if a player has a high batting average, then he probably has a high BABIP, particularly since home run hitting alone (home runs being excluded from BABIP) can’t by itself contribute that much to a high BA.

In addition, as strike out rates have soared, batting averages have plummeted. Sure, sure: a player who strikes out can’t get a hit, so more strike outs entail lower averages.

But the natural assumption would be, then, that as strikeouts go up and batting average down, BABIP should either fall as well or remain neutral. One might conjecture that as it becomes harder to make any contact on rocketing fastballs, it probably also becomes harder to make good contact. If so, then as BA plummets, BABIP should decline too. Alternatively (and I think more plausibly), one might expect the shift upward in strikeouts and corresponding downward shift in batting averages to have a negligible effect on BABIP: those trends wouldn’t change the combined impact that fielding proficiency, weak pitcher influence, and chance have historically all had.

The thing one really wouldn’t anticipate, or at least I sure wouldn’t, is that BABIP would all of a sudden declare its complete liberation from batting averages and explode upward along with strike outs. But that’s plainly what has happened over the last three decades or so.

What explains that?

There are a number of possibilities that I can think of.

1. Fielding proficiency has declined, so more balls in play now result in hits.

That strikes me as pretty unlikely. Fielding proficiency matters less than it used to as a source of variance in runs allowed. But that is pretty convincingly tied to fielding-independent pitching (FIP) mattering more: strikeouts account for more outs, homeruns for more runs, making fielding less and less important.

Moreover, if a drop in global fielding proficiency explained rising BABIP, then variance in fielding quality ought to explain even more variance in team oBABIP: against the background of ever worsening defenders, teams with skilled glovemen would get an even bigger advantage. But that’s not what we see. Indeed, the contribution that differences in fielding proficiency make to differences in oBABIP across teams has dropped, too, along with the increase in strike outs. . . . What the . . . ?

By the way, the massive disparity between BA and BABIP didn’t meaningfully slow down during the modern “shift era.” Between 2017 and 2019, the shift doubled—from 12% to 24% —and BABIP fell a trivial 2 points (from .300 to .298). It’s surging strikeouts, not any innovations in fielding, that have pushed BAs down.

2. Balls hit off of pitchers who strike out a lot of hitters are harder to field.

2. Balls hit off of pitchers who strike out a lot of hitters are harder to field.

That seemed more plausible to me as a conjecture. But I don’t think the data bear it out.

Again, differences in fielding proficiency ought to be having a bigger impact on oBABIP if in fact balls hit in play are now harder to field. But as noted, the trend is in the opposite direction: greater fielding proficiency is yielding a smaller return, not only as a total contribution to runs allowed overall, but to containing oBABIP as well. (That doesn’t mean, though, that balls hit in play are now easier to field, or BABIP would be declining, not increasing!)

3. Players who hit lots of home runs also hit harder to field balls

Is that possible?

Home runs are definitely up, along with strike out rates. So I guess it could be that today’s sluggers are smoking harder to field line drives and the like, driving up BABIP.

But again, if this were so—if a significant number of hard-hit balls had become more difficult to handle than used to be the case—then good fielding would now be even more consequential than in times past. That’s not true, as I’ve already explained.

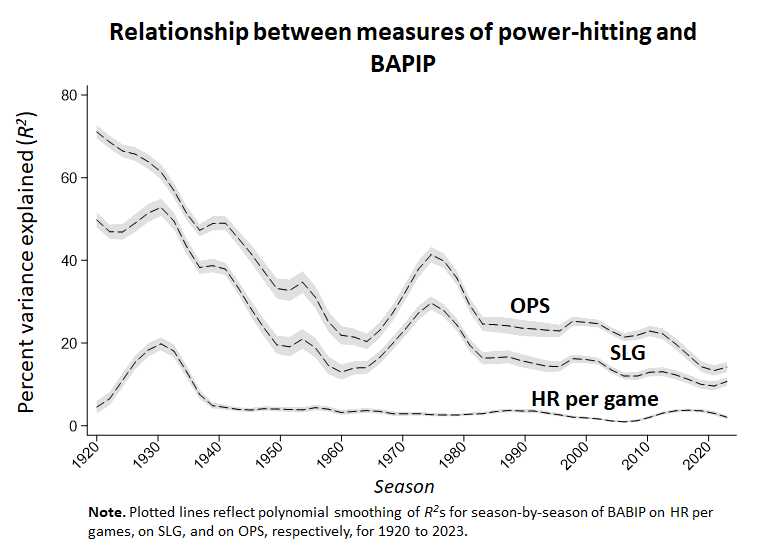

In addition, if power mongers smashed balls that are harder to field, there should be a positive correlation between home run rates, SLG, and OPS (still the most powerful measure of run production), on the one hand, and BABIP, on the other, particularly at the individual player level.

But that turns out not to be true either.

But that turns out not to be true either.

I’ve emptied my data clip here, and I’ve gotten nowhere!

I can’t say this puzzle is driving me insane. Because I’m pretty sure I was insane already—and indeed, that being obsessed with this issue is a symptom of that.

But this is a really frustrating and obsessing me at the same time the way, say, a hangnail or sore tooth does.

I’m going keep digging, and I’m worried I’ll never emerge.

Can anyone please, please help me??