In a series of recent posts, including ones detailing my ongoing project to form a valid estimate of the impact of pitchers’ “ball in play” propensities on runs allowed (keep your eyes peeled for an enhanced, BIP_RBA_2.0), I’ve been using the metric FIPr. I thought I might as well spell out why I’m using it as opposed to the conventional FIP metric available on Baseball Reference and FanGraphs.

In a series of recent posts, including ones detailing my ongoing project to form a valid estimate of the impact of pitchers’ “ball in play” propensities on runs allowed (keep your eyes peeled for an enhanced, BIP_RBA_2.0), I’ve been using the metric FIPr. I thought I might as well spell out why I’m using it as opposed to the conventional FIP metric available on Baseball Reference and FanGraphs.

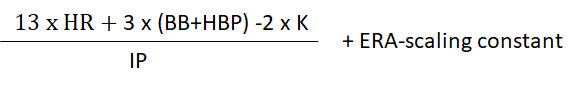

To start, what’s the difference between them? Well, conventional FIP applies invariant non-regression based weights to pitchers’ rates of home-runs allowed, walks, strikeouts, and hit batters and then modifies the sum by an ERA-mimicking constant. FIPr, in contrast, uses linear regression to relate the impact of those elements of performance to runs allowed per game on a season-by-season basis.

I’ll identify what I see as three advantages of FIPr over FIP—in ascending level of importance

First, FIPr dispenses with the information-effacing constant FIP uses to make a pitcher’s fielding-independent pitching “look like” ERA. The whole reason for having FIP is that ERA, which conflates the contributions of pitching and fielding to run avoidance, is recognized to be an invalid measure of pitching proficiency. So I can’t understand why FIP scores are altered to make them “feel like” that very metric.

The reason can’t be that such a transformation is necessary to make FIP comprehensible. FIPr generates a straightforward estimate of the number of runs a pitcher is personally “responsible for” per game. It might be 3.63 or 2.86 or 5.21, etc. That’s how many runs he would be expected to yield per 9 innings based on the run-related outcomes that he controls, independently of the proficiency of the fielders who back him up.

That’s exactly what those who are trying to measure pitcher performance want to know. It’s a bad idea, in my opinion, to obscure that information with a transformation that tries to make this metric mimic one everybody agrees is uninformative.

That’s exactly what those who are trying to measure pitcher performance want to know. It’s a bad idea, in my opinion, to obscure that information with a transformation that tries to make this metric mimic one everybody agrees is uninformative.

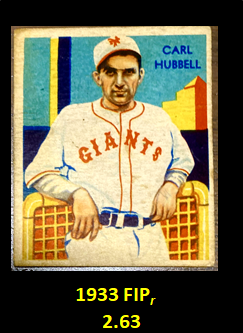

(One note: because game conditions shift, it’s essential to standardize FIPr—or any other measure of baseball performance—if one wants to compare player performances over time.)

Second, FIPr’s weights are genuinely empirical.

From what I can tell (the information is not easily hunted down), the fixed weights that inform FIP were derived from run-expectancy values associated, at one time or another, with the pitching outcome measures FIP comprises. If that’s how they were determined, then FIP ignores the covariance of these measures; unless that’s taken into account—as it is with multivariate regression—the sum of the weighted variables will systematically misestimate the number of runs a pitcher is personally responsible for.

In addition, fixed weights, no matter how derived, will over time generate estimates that are disconnected from empirical reality.

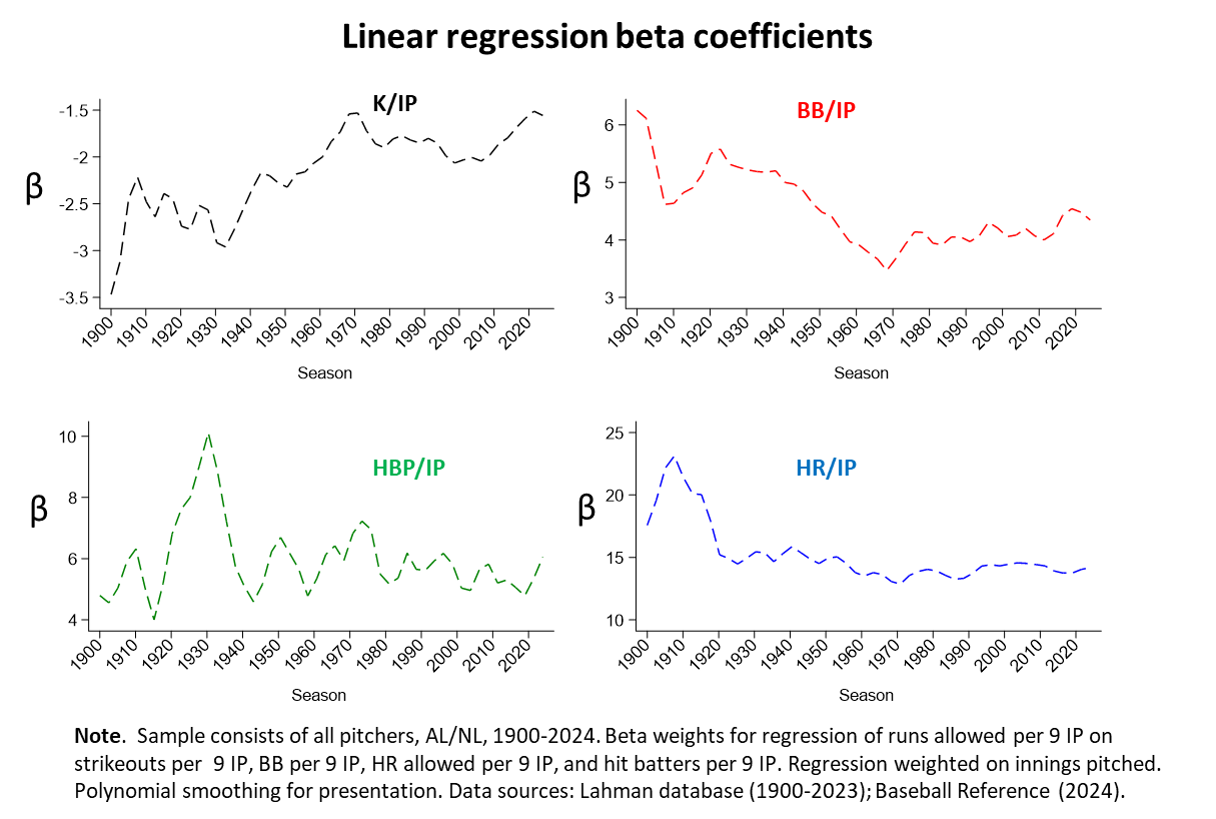

Run-scoring rises and falls as game conditions change. The contributions that the elements of fielding-independent pitching make to suppressing runs can thus be expected to vary over time too.

Here’s a summary of the historical paths of regression-derived beta weights for home-runs allowed, strikeouts, walks, and hit-batters (all calculated as rates) in relation to runs allowed per game.

A measure that ignores fluctuations like these is certain to generate systematically inaccurate estimates of a pitcher’s fielding-independent responsibility for runs allowed.

FIPr doesn’t have that problem. By design, it tracks the evolving significance of the rates of home-runs given up, strikeouts thrown, walks yielded, and batters hit with the greatest possible degree of fidelity.

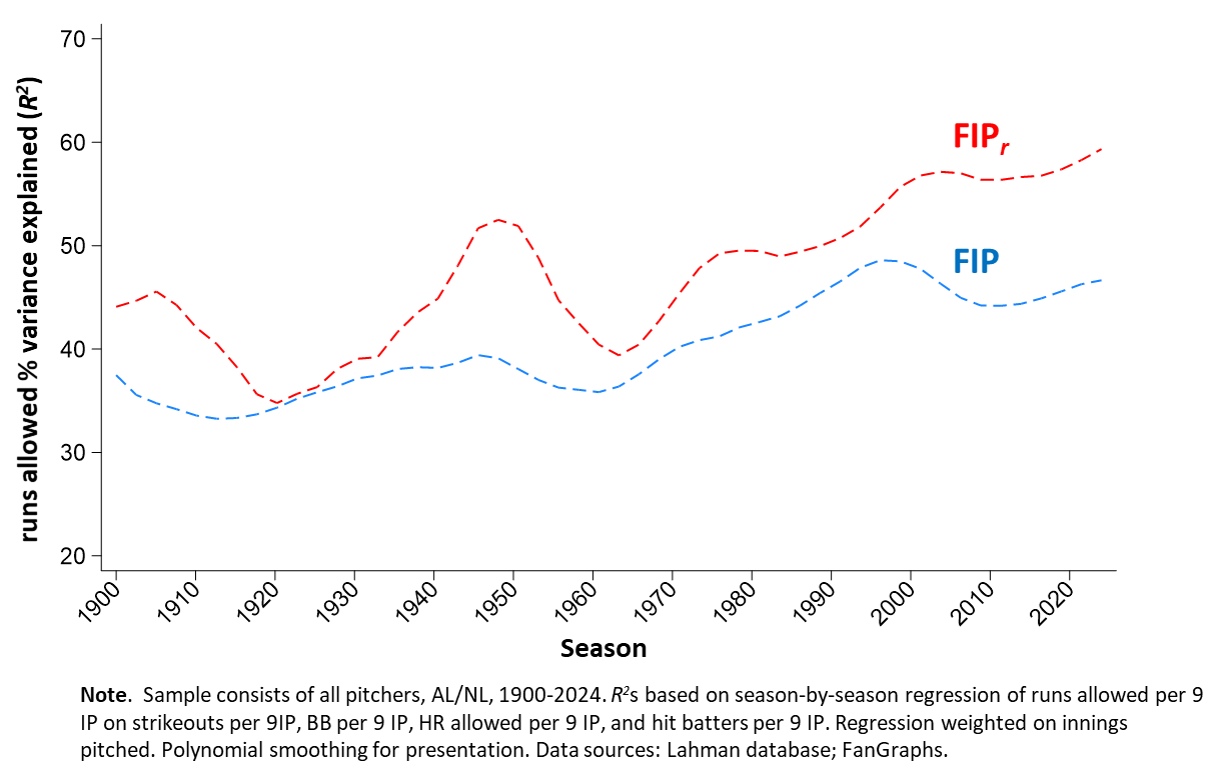

Third and most decisively, FIPr’s explanatory power exceeds FIP’s. This is a direct result of substituting empirically derived, season-by-season multivariate regression weights for conventional FIP’s static, theoretical ones.

So there you go. This is why I use FIPr, and why I’d recommend that others who are interested in estimating pitchers’ “personal responsibility” for opponent runs per game—whether for its own sake or for use in analyses that combine that information with other elements of run avoidance (team fielding, “ball in play” propensities, etc.)—use it too.

I’ve posted season-by-season weights, along with the data used for this post, in the data library.