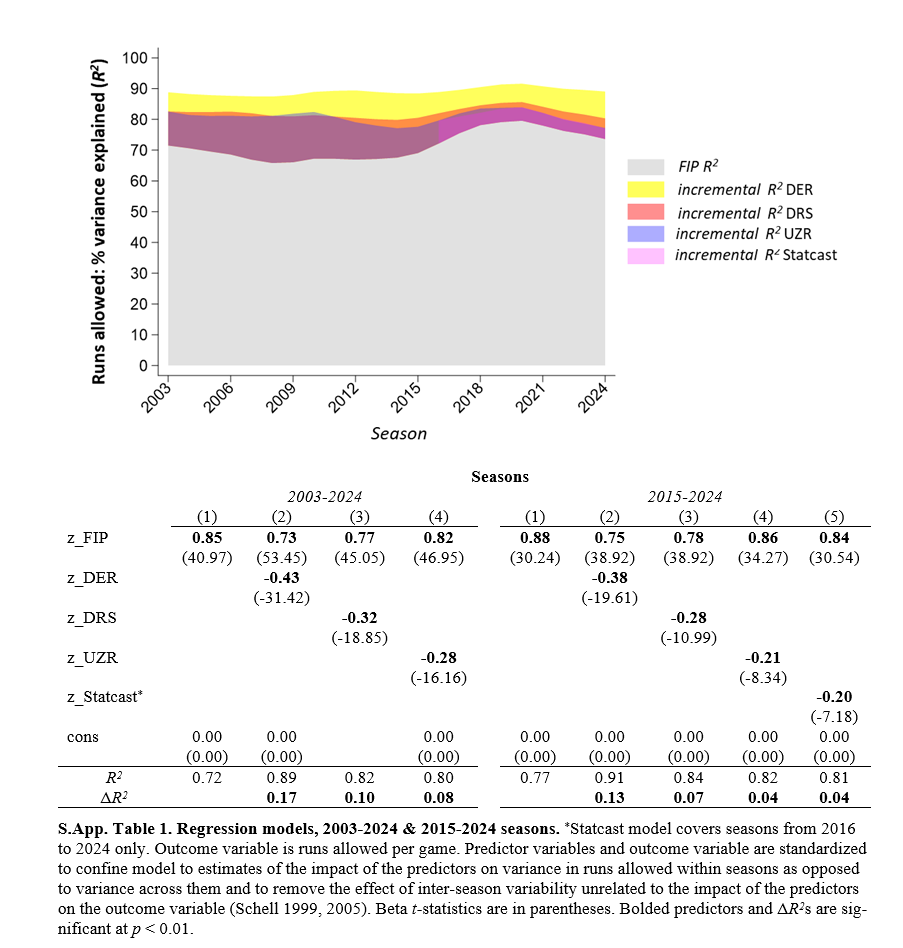

This was something that for sure needed inclusion in the fielding paper: an assessment of what Statcast metrics have to say about “fielding shrinkage.” They say: “yup, unh huh, fielding doesn’t matter too much anymore.”

Beyond that, the insight gleaned from adding Statcast data is that Statcast’s fielding measure is not any better than others. Indeed, it explains less variance in team runs allowed than either Smith’s DER (Defensive Efficiency Record; he uses DER as prefix, and I’m calling his measure that now to distinguish it from “Outs Above Average” label Statcast also uses) or Fielding Bible’s Defensive Runs Saved. The same as Ultimate Zone Rating, another digital metric examined in the paper.

So in other words it’s not how big your data are that matters; it’s what you do with them that counts.

Take a look for yourself:

Or better, read the new draft. Tell me what you think of it so that I can make it better!