Everyone knows (and is correct to believe) that Brooks Robinson is the greatest fielding third baseman ever. But how should all the other major leaguers who’ve manned the hot corner be ranked in fielding skill?

Everyone knows (and is correct to believe) that Brooks Robinson is the greatest fielding third baseman ever. But how should all the other major leaguers who’ve manned the hot corner be ranked in fielding skill?

This is another topic suited for illustrating the impact of rfield inflation. Three of the next four places on Baseball Reference’s list of all-time position leaders in runs saved are occupied by third basemen who played either most of or their entire careers after the late 1990s: Adrian Beltré, Scott Rolen, and the still active Nolan Arenado. There is thus a high likelihood that the impact of their performances have been overstated.

“Rfield inflation” refers to the overvaluation of the consequence of fielding proficiency in the metrics used to calculate player WAR.

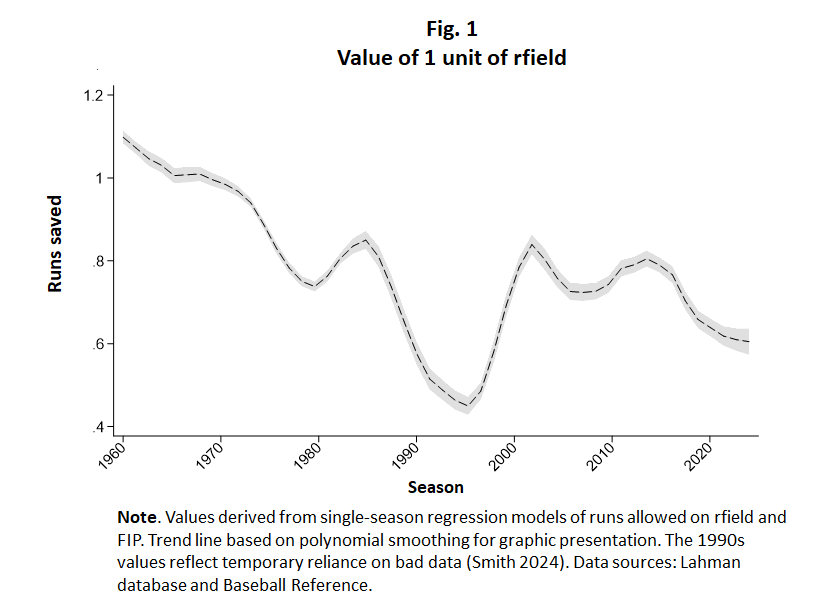

As can be seen, in the 1960s, a unit of “rfield” was worth about what it is advertised to be: 1 run. By the time the millennium arrived, however, the value of this measure was in free fall. In the 2024 season, a unit of rfield was worth only 0.50 runs saved. (The beginning of rfield’s descent is not perfectly clear: the temporary influence of invalid data in retrosheets renders the rfield unreliable for much of the 1990s (Smith [2024]).

Rfield inflation is linked, although only indirectly, to the general decline of the significance of fielding in the major leagues. As strikeouts and home runs have become more and more important, fielding proficiency has become less and less so.

Rfield inflation is linked, although only indirectly, to the general decline of the significance of fielding in the major leagues. As strikeouts and home runs have become more and more important, fielding proficiency has become less and less so.

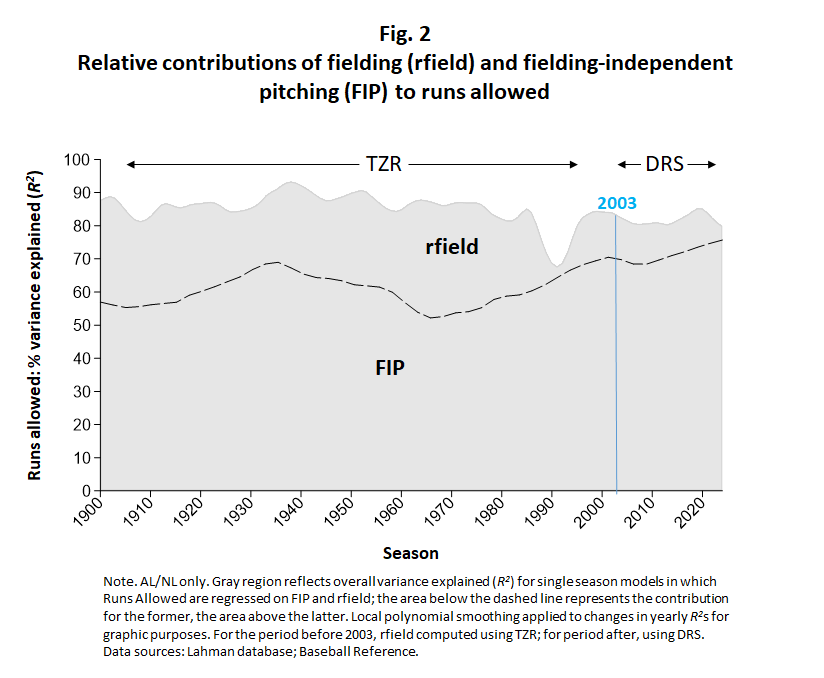

Throughout most of the twentieth century, differences in the quality of major league teams’ fielding proficiency—as measured by Sean Smith’s pathbreaking Total Zone Runs—routinely accounted for 30% to 35% of the variance in runs allowed. Since 2003, differences in fielding proficiency, measured by Fielding Bible’s Defensive Runs Saved, account for less than 10%.

The opposite trend occurred with “fielding independent pitching” or FIP, which is driven principally by strike outs and home runs. From around 55% through the 1980s, FIP today accounts for closer to 75% of the variance in runs allowed at the team level. In effect, FIP engorged itself, swallowing up the impact that fielding had once had.

The opposite trend occurred with “fielding independent pitching” or FIP, which is driven principally by strike outs and home runs. From around 55% through the 1980s, FIP today accounts for closer to 75% of the variance in runs allowed at the team level. In effect, FIP engorged itself, swallowing up the impact that fielding had once had.

Compared to baseball as it was played for most of the twentieth century, good fielding today merits less credit, and bad fielding less blame, for differences in teams’ capacity to stave off runs.

But that development could actually be accounted for by appropriately adjusting measures of the runs-saved effect of fielding quality. It’s the failure to recalibrate the fielding element of WAR over the course of FIP’s ascendance—and not any defect in either TZR or DRS, both of which are demonstrably valid—that accounts for rfield inflation.

But that development could actually be accounted for by appropriately adjusting measures of the runs-saved effect of fielding quality. It’s the failure to recalibrate the fielding element of WAR over the course of FIP’s ascendance—and not any defect in either TZR or DRS, both of which are demonstrably valid—that accounts for rfield inflation.

Let’s take a look at what this means for judging the merits of the game’s all-time best third basemen.

Like I said, forget Brooks Robinson. He played before the era of rfield inflation, and in any case is too far ahead of anyone else to be affected by any adjustments.

But as for downstream bragging rights, the significance of rfield inflation is profound.

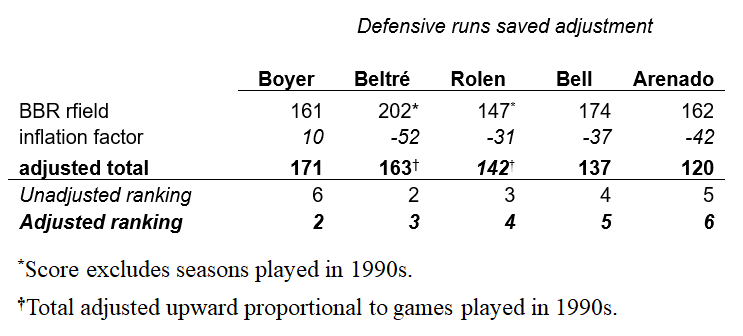

I examined its effect on the calculation of runs saved credited to Beltré, Rolen, and Arenado, as well as Buddy Bell and Clete Boyer. The latter two are the pre ’90s third basemen whose all-time rankings (4th and 6th, respectively, on BBR’s rfield list) are most likely to have been eclipsed as a result of rfield inflation.

To correct for rfield inflation, I multiplied the runs-saved score awarded to each player every season by the actual runs-saved values for the relevant season as determined by the regression models used to generate Figure 1.

Because BBR’s rfield scores are unreliable for the 1990s, Rolen’s scores for 1996-99 and Beltré’s for 1998-99 are ignored and their final adjusted scores adjusted upward by an amount proportional to the (small) fraction of their total career games played during those seasons.

Here are the results:

In short, Clete Boyer climbs from sixth to second on the all-time fielding-runs saved list. Boyer leapfrogs Beltré, Rolen, and Arenado. He also overtakes Bell, both as a result of a very modest undervaluation of TZR units during a part of his career and only a slightly higher degree of overvaluation in the ’70s and ’80.

If one goal of compiling scores such as these is to promote historical comparisons, then the impact of rfield inflation has indeed deprived Boyer of his due recognition as the second best third baseman in AL/NL history.

Beyond that, I don’t think there are any “big lessons” to be learned. Just the obvious one that that metrics like those used to assess fielding performance should be empirically tested at the outset and then recalibrated as necessary as conditions in the game change, as they inevitably—indeed, often dramatically—do. I’m sure no one would disagree with that!

Anyhow, that’s my provisional as always conclusion. Take a look yourself at the data and analysis scripts, and tell me if you see something else!